Firelight Bird Dogs

Monday, May 31, 2021

For Memorial Day: Elegy for a Sportsman

Saturday, May 29, 2021

Burrs Under the Saddle

Sweet Jane originally came from a reclaimed strip mine commons somewhere in deepest, darkest Appalachia. Apparently, mountain folk there still mark their livestock before turning them out on those highland community pastures. To that end, Sweet Jane has a notch cut in the tip of each of her ears.

She also has scars I find every time I groom her, ridges of crusted skin lying across her chest where some cretin used extreme measures to tie her head at an angle to make her gait.

She came from a notorious horse auction to a trader here in Ohio, sold as a 9 year old. I bought her at a deserted fairgrounds on a cold January afternoon during a pandemic, the talisman I needed for assurance that spring and warmth and health for my neighbors and me was truly on the way.

My vet and my farrier are certain she is closer to 15 years old. Doesn't matter. I'd cover my age if I could.

She didn't come with a name. She earned it standing in a snowstorm, sharing hay I had forked to her. A donkey the other mares had bullied away was feeding at her side. Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground were on the satellite radio in the truck. Sweet Jane.

She stands patiently to be saddled. This morning, doing my "pre-flight check" of tack, I found a spiny ball of burdock under the saddle pad. At the least, that nasty bit of nature's splendor would have made Sweet Jane uncomfortable, but who knows? Maybe Sweet Jane wouldn't have been so sweet with that burr digging into her flank and I'd have gotten another lesson in just how little a 66-year-old carcass bounces when tossed to the turf.

Flipping that prickly ball into the barn trash bin, it occurred to me that maybe I could use a little de-burring now and then, a quick airing of grievances beyond Seinfeld's "Festivus" traditions to keep them from rubbing me absolutely raw. Perhaps a list of annoyances is in order, but in no particular order... especially the self-inflicted ones:

1. When I give my bird dog a command more than once. "Here, Gunbutt. Gunbutt, come! Gunbutt! You come HERE to me!" I don't need Baer testing to know why my dogs seem hearing impaired.

2. Mindless generalized barking for attention...in dogs and in humans.

3. Psuedo conversations that open with, "I hunt with a Chocolate Lab..." "My chestnut tri-colored setter..." "Our Golden Doodle..." (My opposition to this would be suspended if I were being offered a stately mold of retriever-shaped gourmet chocolate. Different deal).

4. People who wheel into my barnyard, wave a greeting, and turn their dogs out, thinking I'll be delighted to see them (the dogs, that is) irrigate my pitiful flower beds, send the homing pigeons into hysterics, rouse my dogs who might be kenneled at the time or worse, confront those who are lounging on their own porch or in their own yard, stir up the horses: You know, "running free" like they can't in suburbia, like they think mine do here...5. Professional hunting guides taking grouse and woodcock clients on public tracts of land. Not cool.

6. Dog breed cultists. Cultists of particular strains of dog breeds. Shotgun model cultists. Gear cultists. Cultists using any or all of the above (complete with demurely referred to price points) as credentials.

7. Dog traders. Wheeler-dealers. Volume breeders, especially those breeding strictly on pedigree.

8. I think bird dog chat room/Facebook group experts would make the list, except I only ventured there once, so those are imaginary burrs...but annoying nonetheless.

9. Disrespectful commentary that begins with "With all due respect..." or arrogant punditry that starts, "In my humble opinion..." Go away.

10. The "Whack 'Em/Stack 'Em/Kodak 'Em" crowd with their body count tailgate snapshots of "a big day afield" (been there, done that, sold 'em with articles, shame on me).

11. Speaking of photos, portraits of dogs on point taken from the rear, giving ol' Gunbutt the appearance of having but one eye.

12. Folks who put their dogs up after a run without drying them off, then checking ears, eyes, feet, "leg pits," etc.

13. Biters. Including dogs.

14. "Waterproof" anything that really isn't.

15. Dull pocketknives, humans, books, dogs, films.

16. Waxing: waxed cotton, trucks, skis, body parts.

17. Cheap (and expensive) bootlaces that won't stay laced.

18. Harness-style "collars" I see folks using so their Husky or Bichon-Friese or Sheepadoodle can more easily drag their doting humans down the pavement.

19. Covert cannabis cultivation in public land grouse coverts (except at harvest time).

20. Folks who don't pick up spent shot shells in the field.

21. Ill mannered people with dogs in outdoor restaurants; ill-mannered dogs with clueless people in outdoor restaurants.

22. Paying more attention to our hand-held electronics than our dogs' hunt.

23. Three-inch 28-gauge shotshells...and shotguns chambered for them. Wingshooting's best example of when more is less.

24. Retriever gun dogs wearing buoyancy vests on quiet water.

25. Whiskey in flavors. Competitive "hunts." Both are fake.

26. Self-absorbed, curmudgeonly twits who make lists of pet peeves, most of which they've been guilty of themselves. But maybe sometimes a good de-burring is good for both saddle and soul.

Sunday, May 23, 2021

A Breath for Seth

By Randy Lawrence

"Is it Friday? Wow, what a week! I thought I was supposed to be down here in Ohio to kind of take a vacay from hormonal madness. But noooooooooooooo... A big truck wheels in, I'm introduced to a brazen female from 'way outta town, and suddenly I'm supposed to...well...you know, 'Make Whoopie'.

Save the wisecracks. It ain't easy bein' stud dog me.

'Specially when they are really pushy like this one. I mean, I don't blame her. I got it all goin' on. But seriously! At one point, she was playing so rough I had to jump up on the dog house to escape. Not a dignified move in the least, but hey...enough is enough!

All the while in the background, the humans are talking in code, like they don't trust me to know what's really up. LH spikes. All kinds of numbers. Debating about ovulating... all as I'm over here getting a tail whipping up in my grill, dealing with rude confusion over who mounts whom and outrageous marking all over my playground area...and then, The Great Mystery clicks, everything gets crazy and BOOM!

Suddenly I can't move, I'm terrified that she's going to, and I'm like frantic, lookin' for my human. 'Dude! Lil' help over here?'

In a blink, he has hold of my collar and hers, telling me to chill, that it's all good.

'All good for you, maybe, you and the other human, grinning like fools and bumpin' knuckles...but do you understand what's happened here?'

It's weird...like I always forget about that awkward push-me/pull-you deal. It's part of the job, but take it from ol' Sethie - it AIN'T the good time part.

Afterward, there was happy talk and hand shakes between humans, lots of ear scratching for me, so I suppose we did ok, she and I. But I gotta tell ya...when the Other Human clipped a lead on that lady-what-wasn't-a-lady and walked her out to her truck, I was relieved to be back inside and racked on the cool kitchen floor.

I left a wake-up call for when it's time to go hang out with my boyz over in the main yard. I've never been a big kiss 'n' tell kinda dog, but there's a Pyrenees in there who acts like 'Great' is his first name. Can't wait for him to ask, 'Whaddya been doin' behind the house, Seth?'

Lemme tell you about great, white dog...

Remember Your First Time?

I went to the dogs at age 27. It's important to note that until then, I'd been squirrel and rabbit hunting maybe a dozen times. I had never been bird hunting, never seen a pointing dog work. In fact, the first and only gun dog I'd been around, growing up, was a Louisiana Delta Labrador in exile, here in Ohio only because his human was in on our brief oil boom in the mid-60's.

The dog repeatedly ran away from his yard in a nearby subdivision because he loved to swim in the big cement cattle trough we kept for our milk cows. I only knew he was a gun dog because the man in the wide black cowboy hat who talked like Justin Wilson kept coming to get "Blackie." Every time he visited, he bragged about the ducks he and Blackie shot "back home" before loading the dog into a shiny new diesel pickup and rumbling away.

I got slower and slower about calling Mr. Big Hat Ragsdale to report Blackie AWOL. After all, the big dog loved to ride in the front of our beat up grain truck with my dad when he took a load of ear corn to town to be ground into cow feed. Blackie was the only dog afforded that privilege until the pointer Riley 35 years later.

Dad would stand talking to the dusty feed mill workers while dumping our corn into the churning trench augers. Blackie always leaned out the window and wagged his tail, hoping someone - anyone - would have time to offer an ear scratch. Inevitably, somebody new would ask, "Is that a full blood Labrador?”

That's when my dad would pounce. "He's full of blood alright."

Side-splitting farmer humor never gets old.

Whenever Blackie and I were alone, waiting on Mr. Ragsdale to come fetch him, I would wrap my arms around the Lab's burly chest and bury my face behind his silky ears. Blackie always smelled musky, very different from our farm dogs. Well...musky, with the slight cachet of cow trough algae.

Fast forward nearly two decades, and I'm teaching, I am coaching, but something is still missing. I accepted an invitation to spend a week on a shooting preserve. Every morning, I raptly watched my cousin train English Setters, German Shorthairs, Brittany Spaniels (in those days), English Pointers, and Gordon Setters. I came home burning up with a fever for hunting over a full-blooded gun dog of my own

During my school lunch hour, I would slip out of the cigarette smoke and constant chatter of the teachers' lounge and study the dog ads in the back of the outdoor magazines. It was a while before I nerved up enough to call a man in Michigan and reserve an English setter puppy "from grouse dog lines."

I did this because my new brother-in-law and his brother Lyle talked endlessly about jump shooting ruffed grouse near their hunting cabin in West Virginia. I figured that if I had a dog "from grouse dog lines," maybe they'd invite me to go grouse hunting.

But while waiting on my puppy to be born, I decided I needed a shotgun. I still had the single shot, hammer 20-gauge my parents had reluctantly purchased for my 17th birthday. But a careful survey showed neither Ted Trueblood nor Bob Brister nor George Bird Evans, Burt Spiller, or Tap Tapply toted a gun like that through the grouse woods.

I settled for a second hand Savage 330 over-under from the village gunshop (a) because it was made in Italy, (b) I knew Italian shotguns were good but I couldn't afford a Beretta, and (c) I didn't know where in the world to find a three-shot, 12-gauge Win-Lite Model 59 autoloader that author Frank Woolner, in my library copy of Grouse and Grouse Shooting, touted as the penultimate grouse killing weapon.

I studied Woolner's book like it was the Torah. Frank had lopped the gun's fiberglass barrel to make a 23-inch cylinder. He sliced off the pistol grip, then circumsized the forearm to make the little gun even lighter to carry and faster to bring into play.

Fifty-one years after the publication of Grouse and Grouse Hunting, shooters still rhapsodize about a "Woolnerized" Model 59. But back then, I didn't think I was up to all of that DIY surgery, though I was totally on board with the "single sighting plane" of Woolner's autoloading shotgun.

"Single sighting plane" was a concept I had pulled from a Gene Hill essay. The expression posited that the narrow reference point of one barrel made for more precise alignment between gun and target.

Never mind that wingshooters don't "sight," nor even register the barrel(s) other than as a peripheral blur. One barrel or two, practically speaking, is irrelevant. But there I was, a fledgling bird gunner, looking for an edge. Gene Hill wrote it. I believed it. That settled it.

Thankfully, that Savage 330 sported a "single sighting plane." I put the $300 double gun on lay-away and paid on it every time my teacher's check hit the bank. I had my puppy endlessly pointing a wing on a string before I had my first bird gun paid off.

It would make a better story if I could say I shot my first grouse over a point by the puppy I named "Drummer." In fact, it would make a 'way better story if I wrote that I shot my first grouse over a point. In fact, I didn't do either.

By the time I had a dog and gun of my own, Lyle had caught the bug, too. He bought a well-started pointer with the big money he made driving a tow motor at Honda. We began making the five hour round trips to southeastern Ohio and into West Virginia together.

Lyle and I quickly learned that shooting grouse only over a green dog's points meant that we wouldn't shoot very many (read "maybe not any") ...and that was unacceptable to both of us. What's the point of going grouse hunting except to kill grouse and bring them home and spread their fans to astound the flatlanders before overcooking them in cream of mushroom soup and pretending they are delicious?

I'm Ok with not remembering the first grouse I killed with that clunky Italian-made Savage gun. All I know is that the bird wasn't sitting in a tree. Gene Hill had written such practices were not sporting.

Savage Model 330

But I am sad that I do not remember the first grouse I killed over a point. I'm certain it wasn't over Drummer, who, under my over-wrought training and handling, would lie down on point and did not hold a grouse for the gun for several long seasons. I imagine it was over Lyle's pointer, and I'm certain I didn't believe it when I saw the bird tumble.I can safely say that I probably raced Lyle's cretinous jaws-of-steel dog to the fall, and that my friend probably had to listen to my play by play on a loop during the long drive back north. Garrulous golfers at the 19th hole have nothing on wingshooters.

Even more certain am I that once I was home, I spread that bird's tail fan over and over, holding it for Drummer to smell like a bloodhound owner sharing a sniff of a fugitive's underwear with his trusty canine cohort.

Trust me when I say that when nobody was looking, I surely buried my own nose in those blue black ruff feathers. I'm sure they smelled a bit musky...with not even a hint of cow trough algae.

Saturday, May 22, 2021

Rookie Year

by Lynn Dee Galey

Born in a small Maine

cabin in the dead of winter, Firelight Setter pups Seth and Sally never saw bare ground until they had

made the 1600 mile journey to our new home in Kansas, nicknamed the Coyote Den

for both the address and the wild dog songs heard close by on many

nights. For 26 hours Seth and his sister Sally rode crated next to

me on the bench seat of the moving truck rental. I drove and the

three of us howled sporadically, sometimes to songs on the radio, sometimes

just to let the world know we were still there.

It was spring in Kansas, and the two pups spent their days romping

the fenced acres of our new home and discovering that adult dogs, both

their English relatives and their new partners, a brace of bob-tailed

French Brittany boys, tolerated puppies but that their ears

and tails were not chew toys. Soon enough the pups learned canine social

skills and could relax in the company of the pack or at least knew enough to

stay out of their seniors’ way when youthful energy brought on fits of

roughhousing and tearing around.

With September comes a

change in the air as everyone is loaded into the truck topper, eight dogs

between my hunting partner and me: five English Setters, two French Brittanys

and most importantly, the pack ruler Worf, a fourteen-year old

miniature Dachshund who travels on his throne, a dog bed nestled on the front

console of the crew cab. The adult bird dogs are energized. They

had seen the guns and boots loaded and the travel trailer hitched up, as road

veterans they know to curl quietly in their kennel boxes in the topper. A

few stern glares and rumbles from their mother through the inside bars of the

boxes tells the Setter pups that they too need to settle down and enjoy

the ride.

The long hours of

driving to the northern plains are dotted with quick stops for diesel and to

air out the dogs. Seth and Sally quickly learn the road rule that each dog is

given about two minutes to tend to its business before being loaded back up -

no dawdling or smelling the roses allowed. At long last the blacktop

roads fall behind, and the dusty gravel leads us to the far reaches of a remote

ranch with only antelope and cattle - and hopefully gamebirds - as neighbors. When the veteran dogs are lifted down from

their boxes, their muzzles turn into the ever present wind, their eyes closed

slightly to savor the rich scents and promise of this land.

With the dawn of each

new day, amid whiffs of sage and the tawny browns of grassy moguls, we put down

a mix of three or four dogs in our search for Hungarian Partridge and

Sharp-tailed Grouse. With faith in good breeding and instinct, I run the

7 month old pups with adults in this wide open classroom so that they can learn

by doing, wild birds serving as both lesson and instructor.

On the first day the

pups fall behind as the adults stretch out over the hills and they entertain themselves with

Montana-sized pup toys - the white washed bones of a cow skeleton from the

bottom of a basin. Proudly they carry their finds all the way back

to the truck. No comment by my long-striding, plains hunting partner regarding

us New Englanders on his turf, but I see his raised eyebrow and slight shaking

of his head, questioning the potential of these long-tail clowns.

But quickly the instincts

in the pups awaken, and they cut their bird dog teeth in the big time, Big Sky

country. It's not easy being the new kids on a well oiled team, and time and

again the puppies are a minute late or 100 yards off from having finds of their

own.

But finally, breeding

meets opportunity.

I walk up over a grassy hill. Halfway down the other slope is a Setter locked down, and yes, this time it's Seth. One of the Frenchmen also sees the puppy with the neon white coat and freezes into a back. The voice in my head quietly thanks him for his usual good form and for respecting that the pup just might have what it takes. On approach I'm hoping that it is a sharptail and not a pheasant, whose season doesn't open for a few weeks.

Walking in through the

rough grass I see the telltale head of a sharpie pop up in the grass, then the

rush of wings and chuckle of flight. The recipe comes together and a

young prairie grouse becomes Seth's first retrieve dropped over his

point.

Mustang Sally is aptly

named and sows a few wild oats before settling in herself. She shows her

strong nose one day when a light breeze pulls her up and over a long

hill. In anticipation, her senior Frenchman bracemate and I start up the

hill after her, hoping for a back and a position for a shot, only to be

disappointed when instead a large group of grouse come flying over our heads

with that little filly in hot pursuit.

With that chase in mind

she is hunted solo the next day in thick, high grass to her withers that might

slow her down a bit. She has to work for it in a field that produces only

a single find. Sally pulls up into a

solid puppy point and holds as I flush the bird. My partner's little

28-gauge usually drops them like a stone but as luck would have it, although he

connects with this bird, it sets its wings and sails before dropping just over

the top of the ridge. In light of the distance and thick grass I have my doubts

about Sally’s ability to make the find, so I head up the hill in that

direction, the puppy ranging well ahead. Before I make the ridgetop, I am

pleasantly surprised to be met by Sally carrying to me her first sharptail, a

wing dramatically flared and covering her eyes.

Lessons taught by the big dogs back home in the

yard and on the road continued into the field: It is a

thing of beauty to see multiple dogs spread out searching for feathered needles

in a 640 acre haystack, but the magic starts when one of

them jinks on a thread of scent, muzzle turned high as the dog becomes more

deliberate in its search. Gunners and dogs who live and spend

considerable time hunting together tune into these birdy signals from a

distance and swing in for the assist. This cooperation from the entire

team often cuts off running birds who are not expecting another "wolf"

to come play "squeeze" and boom, instinct freezes the well bred

birddog either on bird scent or the sight of a bracemate on point. The

innate urge to pin game in place keeps the dogs motionless as the gunner walks

in to flush the birds. That moment is the cumulative final exam of lessons

produced by genes, canine mentors and the birds for whom this is not sport, but

life or death.

The pups learn the hard

way that galloping into these situations that are being finessed by teammates

results in exploding groups of birds with the punishment of no shots fired and

all involved then casting aspersions on the offender. Caution when a team

member is birdy and backing others points is a must; party crashers may hear

their name being used as a discouraging word. Being part of the

pack requires respect and manners and paying attention. Those slow to pick up

on those manners may find themselves with time on the chain gang back at the

RV.

But when all is done

right, prairie grouse hold for a gridlock of dogs, lifting only at the sight

and sound of a gunner walking in. When a shot is fired and a bird falls, the

dogs race for the retrieve. The first one to the bird is the victor who is then

escorted by the others as the grouse is brought to hand.

With the pheasant season

opener comes running ringnecks who taunt and teach puppies a new set of

lessons: there one minute, gone the next. Tail flashing, excitedly

bouncing through the draw, Seth just knows there is a bird there, and

from his trembling stand, he fails to get the joke when the rooster flushes 70

yards away with its laughing cackle. Watching the bewilderment in Seth

makes me laugh out loud along with that rooster.

The prairie weeks pass quickly, and when Seth and Sally and the

rest of the crew return to Kansas it is time to meet Bob. Bobwhite

Quail that is. And Bob has his own rules and playbook. Birds are now found in

brush tangles and along edges of weedy crop fields. Bob and his covey

mates require some throttling down in speed and distance compared to the Big

Sky birds. These 6 ounce delights sit tight like young sharpies in the grass,

but when flushed they jet through timber like miniature rockets. Game on

then to locate singles who always seem to fly across a creek and disappear into

thin air.

The puppies’ pheasant

education translates when Seth locates a covey of quail running along the

bottom of a deep, wooded drainage. When he doesn’t pop back up into sight

along a grass and timber edge I head over to the deep draw where I last saw

him. I can hear the covey's nervous

peeping chirps from below as I pause to contemplate the steep bank for my best

non-neck-breaking descent and gunning position. That’s when I see Seth:

cool with caution, pointing and relocating until the birds finally hold, darned

good stuff for a pup that three months ago was more focused on cattle femurs.

Sally’s own moment came in a

favorite cover nicknamed The Jack Gas cover. We New Englanders tend to

name our covers for easy reference and memory: at this time I choose to not

share the explanation for this one, granting dignity to a great dog named

Jack. I last saw Sally as she weaved through the brush along the barbed

wire that separated this picturesque, hilly CRP field from the neighboring crop

field and when we got to the top of the hill we can see one of the Fr Brits

standing at the edge of the timbered draw below. Unsure of where Sally is

and hoping that she does not stumble into the situation from the wrong side, my

hunting partner and I head down toward the draw. At about 50 yards away a smile comes to my

face as I see that the Fr Brit was not on point, he was actually backing Sally

who was pointing a covey but was well hidden in the brush. I pause to snap the

photo and the little half-masked pup stands solid as I walk in and flush the

covey. A single that swings to the right drops at my shot and is returned to me

by Sally: I swear that Sally and I have matching smiles on our faces as hold

the little cockbird in my hand.

One of the blessings of Kansas

hunting is that it extends through the end of January but finally it is time to

clean and case the gun for the season. Seth and Sally are nearly a year

old as the season closes. In the last 5 months they have built a nice resume

with multiple species of wild birds handled, thousands of miles traveled, and

became civilized members of canine and human groups. As I review the

photos that I took over these months, the memories will come back to life. And

as the pups snooze with the rest of the pack in front of the wood stove, I will

hope that their twitches are a playback of the same memories. Sleep well pups, there is so much yet ahead.

Saturday, May 15, 2021

An Athlete on Spring Break

By Randy Lawrence

At this writing, Firelight Seth is vacationing on the “Rushcreek Riviera” here on my southern Ohio farm. OK. “Vacation” may be a misnomer. Maybe it’s more like a hormonal quarantine as things “heat up” at Firelight Central.

We have learned that when Lynn Dee’s setter harem cycles into season, Seth’s desire to sire can get the better of him, reminding me of my Great Uncle Willie favorite aphorism, “Sex makes fools of us all.”

This may explain in part why Uncle Willie was nearly 80 years a bachelor.

However, it rings sadly true with my pal Seth. The prospect of adding his mooning and moaning to the circus of Firelight Annie’s litter just now starting to open their eyes, trundle about, and climb the walls of their whelping box meant it was time for Seth to head south for the duration.

When Seth visited last, he was recovering from a tough run of circumstances with another owner ( http://www.longhuntersrest.com/gone-to-the-dogs/soul-food ). He needed bathed and fed. He needed to find his legs after months, kennel-bound. He needed his faith in people restored.

By the end of his first stay, he was on his way. In terms of performance, he made a deep impression with powerful, intelligent casts, his intensity on point, and his unquenchable urge to please. His rehab with people? Never a question, from the groomer to the vet to anyone he met. He came back for this recent board 15 lbs. heavier, light years more confident, and an English setter in his absolute physical prime.

Seth sports an athlete’s frame. He is a shorter-coupled, physically balanced dog with plenty of leg and an uncommon way of going: cat footed, nimble, and collected. He laces more open cover with long, reaching strides and virtually punishes the nastier stuff with a strength and commitment made possible by his sturdy physique and refurbished mind. Seth has found birds in the thick and thorny, and he will flat tear it apart to find them.

Seth's tail set is high enough to give him reach and push with his back end, an underestimated aspect of functional conformation. His straight, shorter tail cracks when he works and mark a just-right-for-me 10 o'clock angle when he goes solid on point.

This dog could come off a couple weeks of Montana prairie hunting and be an absolute beast, lean and sinewy with tough feet and the kind of bottom that only belongs to the great steeplechase horses. If the plains grouse and partridge were in any kind of numbers, he’d also have something else: added conviction. To wit, “If I keep pushing, good things will happen.” Such a dog gets around with an edge, a singular purpose - to find a bird to kill with his handler/partner.

Some of us enamored with the classic look/demeanor of certain lines of English setter have sought bigger, slower dogs (1) for their picturesque appearance, and (2) for what we presume will be a closer working, more manageable hunting partner. Surely personal taste and sense of how a hunt should be conducted factor in here, but for my money, I believe we are wide of the mark if we are not constantly on the scout for bloodstock with both “The Look,” and what I might call “Intelligent Burn.”

In class pointing dog work, savvy speed kills. I value the dog with the innate physical tools to cover more ground more quickly, more purposely, in an “Intelligent Burn” - hunting with tractable initiative to likely cover in partnership with the gun. A cagey dog who abruptly goes from 60 to 0 and slams into her points (rather than snuffling and checking and double-checking and then melting into a stand) is going to set more game for the Gun. Those Wham-Bam-Shoot-It-Ma’am points leave birds knowing not whether to hunker or haul tail feathers. Often enough, “hunker” is the choice, giving the Gun a sporting chance to flush.

Saints preserve us from hunting behind some harum-scarum splatterninny careening wild through the woods. It's a Bird Dog (in caps) we're after, a cool running predator who works to the cover and for the Gun...even if it is between bouts of the lovesick blues.

Friday, May 14, 2021

Jewelry for Woodcock

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

For The Record...

The other day, I said something remarkably stupid.

To be fair, I say stupid things every day; my only saving grace is that they are not frequently remarkable. Just stupid.

"I wouldn't buy a dog from someone who didn't keep a hunting diary," I announced airily...to the person who has sold me some of the best gun dogs I've owned in over a decade, a person who resolutely keeps no record of birds moved or points made, let alone any ledger on shots attempted or birds taken.

What followed was a patently pregnant pause giving birth to a more courteous question than I deserved. "Why is that?"

I blurted, “How else do you really know what you're doing?", already aware that Lynn Dee Galey has a firm handle on her dogs' work over the seasons. She simply has never been interested in reducing the experiences to data.

"I never figured you for a numbers guy."

I bristled at that, but kept entering info. "I just like to have a sense of the day," I harrumphed. "Don't you keep track, you know, of how you're doing?"

Suddenly, I could hear Ted Knight's deep baritone from the movie Caddyshack when he asks Ty Webb, the Chevy Chase character, what he shot that day on the golf course.

"Oh, Judge," Ty answers modestly, "I don't keep score."

Knight, in his role as Judge Smails, is aghast. "Then how do you measure yourself with other golfers?"

Of course the movie answer, famously, is "By height." But is that really what we're about when we keep a hunting journal? Measuring?

Well...no. And yes.

The two best grouse hunters I know have a combined record of 95 years hunting with their English setters. Recorded are coverts or sections by name and location. If there are landowners of whom permission was asked, their names are logged in for coming back in the future (or not) or for a thank you note, maybe a Christmas card or small gift. The weather is always marked, too - temps, prevailing winds, precipitation, etc.

The dog work is, of course, central. Time is kept. Points and backs made, birds moved for x number of flushes, perhaps a mention of unusual performances, good and bad. My friends have a complete record of not only every dog they’ve hunted through the decades, but every guest dog that has run with their crew.

From all of that, both men can tell you on good authority how their setters perform under what conditions, over what sort of ground, on which species of birds, at what stage in their career. Those stats afford them an informed perspective on not just individual dogs, but generations of their bloodlines. They know when to cut slack and when maybe a dog as slacking. When either fellow offers an opinion, for example, on likely scenting conditions under certain circumstances, only a fool wouldn't listen.

They keep track of their shooting, too. Each guy knows his percentages of kills to misses on every type of bird over every sort of terrain in all kinds of weather. If either of them shares shooting stats with you, you know you've reached a very rare level of friendship. For them, field shooting is decidedly not something to be measured against the prowess of others.

That’s why God made trap and skeet and sporting clays...so's we can measure us'n's against the other'n. My guys only care what they do in honoring good dog work.

Each one keeps careful record of birds found and birds taken in a specific locale, an important part of his stewardship of wild places and wild game. They know exactly how many times they’ve visited a particular covert during a season and what it's yielded. From that, they can not only decide whether a spot is worth another visit, but also if they need to lay off a particular area altogether, with far more intel than just a vague sense of "enough."

Their journals mark a learning curve of which they’ve never tired. At the end of every season, each fellow tots up the numbers from every outing. Each knows exactly how many hours and days his dogs have actually hunted. They know how many discreet spots they've visited. They know how many bird contacts each dog has logged for the year, as well as how many points, backs, bumps, etc. They make note of how they fared with birds on the run, which braces hunted best together, maybe what game bird had this dog's number or how that dog improved on a species from one year to the next. Every litter they’ve bred over time has been informed by those numbers.

I envy my friends’ file cabinet drawers of hunting journals. They can reach in, pull a particular year and be there again through their notes and numbers. Dogs that have long left them are alive and working again. Faded snapshot memories, faded by years, return in vivid colors.

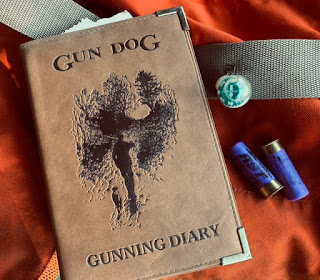

I used my friends’ habit as a model for a number of years but finally gave it up. I have neither the discipline or commitment to keep track of my hunting in that way. Once upon a time, I wrote in a fake leatherette "Gunning Diary" I bought out of a magazine The pages were a soft faux parchment tan. William Harden Foster images decorated the margins.

I wrote in it every night after a hunt during the season, taking notes during the day, then transposing them into the Official Journal when I got home or while sitting at the scarred desk in some backwoods motel near where the birds were. At the end of the day or trip or season, I'd write some sort of assessment about a dog's progress or my shooting woes or the State of Bird Numbers in various ports of call.

I dug it out the other day and was reminded that (a) we traded shotguns a lot in those days; (b) we were not shooting grouse only over points then; (c) I didn’t know what I didn’t know about effective grouse dog performance and couldn’t begin to help my dogs in any meaningful way; and (d) my friend's pointer was constantly either missing or on point or missing and on point. He found most of the birds; we spent a great deal of time trying to find him.

I misplaced that journal for a time, and from then on, record keeping was a catch-as-catch-can exercise that I only did from trip to trip. I stopped the end of the year commentary, and until computers came along to store stuff, whenever I got a nagging itch to keep track, I‘d buy one of those pocket spiral notebooks at a gas station or keep tabs on cocktail napkins. I even started using a little pocket recorder, but then seldom got around to transposing my dictation. Stray pieces of data sometimes got folded in plat books or written on map margins, or slipped into whatever novel I was reading. How many times have I pulled a book from the shelf and an artifact of hunting shorthand falls out?

I have thought the magazine articles and anthology essays and blog posts that see print could serve as some sort of record, but it is absolutely not the same. Narratives cherry pick events; stats are narratives that don’t blink.

I confess that Lynn Dee Galey's reasons for not crunching numbers are maybe more in tune with how I am today. At the risk of slipping into throwback hippie woo-woo here, the experience in the now doesn't need the numbers. She knows from living closely with her dogs for eight generations just who they are, how they've evolved, and what about their performance and personality she's tried to breed on from litter to litter.

A cynic might sneer and label all of that more serendipitous than scientific; that's fine. Cynics make for lousy hunting companions (among lousy other things). Galey doesn't make stuff up, that is, she does not write checks her dogs can't cash. In her own way, she knows who she is, who her dogs are, and represents both with candor and savvy insight. It's a different way of knowing, but by gadfrey, she knows, and it works for her.

For the record, Lynn Dee is also unfailingly generous, even when I am remarkably stupid or when she looks over and I'm punching numbers into my cellie during drives between coverts. Old itches still need scratched from time to time.